Having just read Ron Chernow’s brand new biography, Mark Twain, I found myself stupefied by the amount of research involved in a project that ground out to 1033 pages.

It took me two weeks of guerilla-reading just to get through it (and by that I don’t mean it was a drudge), and the audio book is 44 hours long.

That’s right. An entire work week—plus overtime.

I basically covered my feelings about that book on my podcast here. But I will say this: I’ve read three really great biographies about Twain, and I’m slowly plowing my way through the unedited (although curated) Autobiography that he rigged to release 100 years after his death in 1910 (I Know. I’ve had 15 years to do it and haven’t. I can’t really call myself a “Mark Twain Research Fellow” at my own ersatz university without doing so).

I’ll just say this—Chernow’s book made me feel like I was biographically there during the events in Mark Twain’s life. He doesn’t avoid good or bad aspects of the man. He was certainly no saint, but he was also, admittedly—a sinner.

And even though I was already aware that Twain lost three children and a wife before passing himself, to leave only his daughter Clara (and the source of my own daughter’s name), I didn’t realize the body blows, the timing, the sickness, the afflictions and everything else that came at him in a seemingly orchestrated series of salvos.

Aside from losing an infant son to the weaknesses and afflictions of premature arrival, Twain’s next loss would be his daughter Susy—who would die of Bacterial Meningitis in their Hartford Estate while Twain was overseas on a lecture tour—a tour that was attempting to pull his family out a bankruptcy he caused—his writing acumen, facility with the phrase and preternatural wit never translated into business sense—and his obsessive compulsions for investments drove an otherwise wealthy heritage into the red.

He would never forgive himself.

So when I read this account, the footnoting showed me that Susy had started a biography about her father at age 13, only to have it come to a sudden end—mid-sentence—as the ebbs and flows of life, college, music and transitions simply exemplify a “very last time” moment in time.

The Biography would be ultimately published—and it would include Twain’s commentary and annotations throughout—a posthumous tribute to his daughter, and—as one might guess—an attempt to relive his best years with her by lifting the hood on selected entries and exist in those moments in real time. His brilliant prose draws a beautiful chasm between Susie’s occasional struggle with spelling, and the ridiculous cognitive penchant for written expression she possessed.

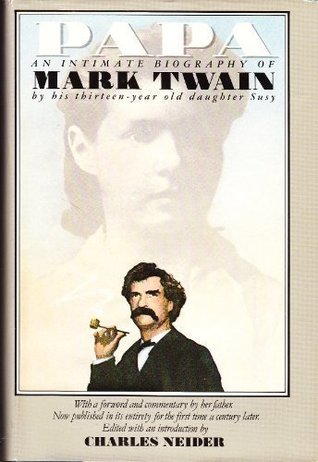

I snagged Papa An Intimate Portrait of MARK TWAIN by his thirteen-year-old-daughter Susy

At the bottom of the dust cover it says With a forward by her father. Now published in its entirely for the first time a century later.

It then concludes with: Edited with an introduction by Charles Neider.

And man, did he EVER—write an introduction—in fact, his 61-page jeremiad takes up an entire quarter of the book.

Now, I covered this issue long ago in this blog post—the Neider’s introduction makes my case for me. I can pile on to him because he passed away in 2001, and therefore is unable to answer any correspondence I might throw his way. So all I have at my disposal is posthumous slander.

His introduction is a long, analytical cross section of the book itself. I actually bailed out of it when I realized how long it was—as I was fully expecting it to ruin the nuances of the back and forth between Susy’s look at her father, and Twain’s heartfelt and funny responses to much of it. The book should stand alone and be read as a posthumous conversation between the two.

I realize that Twain fanatics like me all want to be counted amongst the pantheon (and believe me—I’m flitting around right now trying to find a hot-take on the guy, so I can show up in the bibliographies myself)—but this one is too personal. Neider even included an 1,100 word letter the Susy wrote in the throes of febrile meningococcal delirium—one of the last things Twain ever read of hers. It’s erratic and disjointed, and perhaps a bridge too far in terms of literary decorum here—the biography doesn’t contain this, as it comes to an end long before infirmity was even a concept.

That being said, I’ll cover a couple of things that are endearing. Sure, it’s a 40-year-old book. But I’m not going to spoil it. The observations and twain’s responses are harmonious, and lovely. At one point, Susy draws a bead on her father’s use of vulgarities. I maintain misspellings as they occur:

Papa uses very strong language, but I have an idea not nearly so strong as when he first married mamma. A lady acquaintance of his is rather apt to interrupt what one is saying, and papa told mamma that he thought he should say to the lady’s husband “I am glad Mrs.—–wasn’t present when the Deity said ‘”let ther be light”’

Twain follows up with the following annotation:

It is as I have said before. This is a frank historian. She doesn’t cover up one’s deficiencies but gives them an equal showing with one’s handsomer qualities. Of course I made the remark which she has quoted—and even at this distant day I am still as much as half persuaded that if that lady mentioned had been present when the Creator said “Let there be Light” she would have interrupted him and we shouldn’t ever have got it.

At one point, Susy decides to psychoanalyze her father, and identify the dichotomies in his approach to life:

Papa can make exceedingly bright jokes, and he enjoys funny things, and when he is with people he jokes and laugh a great deal, but still is more interested in earnest books and earnest subjects . . . .He is as much a philosopher than as anything I think, I think he could have done a great deal in that direction if he had studies while young, for he seems to enjoy reasoning out things, no matter what; in a great many directions, he has greater ability than the gifts which have made him famous.

Twain seems flummoxed at Susy’s analytical prowess:

Thus at fourteen she had made up her mind about me, and in no timorous or uncertain terms had set down her reason for her opinion. Fifteen years were to pass before any other critic—except Mr. Howells, I think—was to re-utter that daring opinion and print it. Right or wrong it was a brave position for that little analyser to take. She never withdrew it afterward, nor modified it.

I’ll not dive further into it. Just know it contains an eternity of affection, love and longing in a relatively small book.

Susy’s final entry was this:

July 4. We have arrived in Keokuk after a very pleasant . . . .

And it appears Susy’s effort would never be re-joined.

Twain stares at this final entry, and attempts to rationalize the reasons Susy never brought her pen back to the book. He writes a paragraph so powerful, and speculative, and grieving. Any man with a daughter, living or not can feel the power in the man’s regretful observation.

I’ve always said—his best work is out of the mainstream, and this paragraph is one of his best.

I’ll let you go find it.

Thanks, Ron, that was a really great post. I didn’t know you were a Twain fan. I’m trying to remember where I read that Twain possibly had an illegitimate child, and that some close descendant of Twain whispered to Hal Holbrook that he looked very much like that child. I’m probably mixing up the story, but does anything there ring a bell?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am unsure of this. Although I guess anything is possible. Obviously, Hal Holbrook’s role as an imitator factors into the intrigue of this. I have a 1902 copy of The Innocents Abroad (my favorite book) that Holbrook signed for me. I met him twice. Send me an email; I’m not sure who this is.

LikeLike

It’s Jack Shalom (landmark). Not sure why wp is tagging me as anonymous…but nice post.

LikeLike